W(hatsa)MATA you?

This article is part 1 in a series on wmata. If this is your bag, check out

- Part 1: In which our hero strives to lessen his daily transit rage through SCIENCE

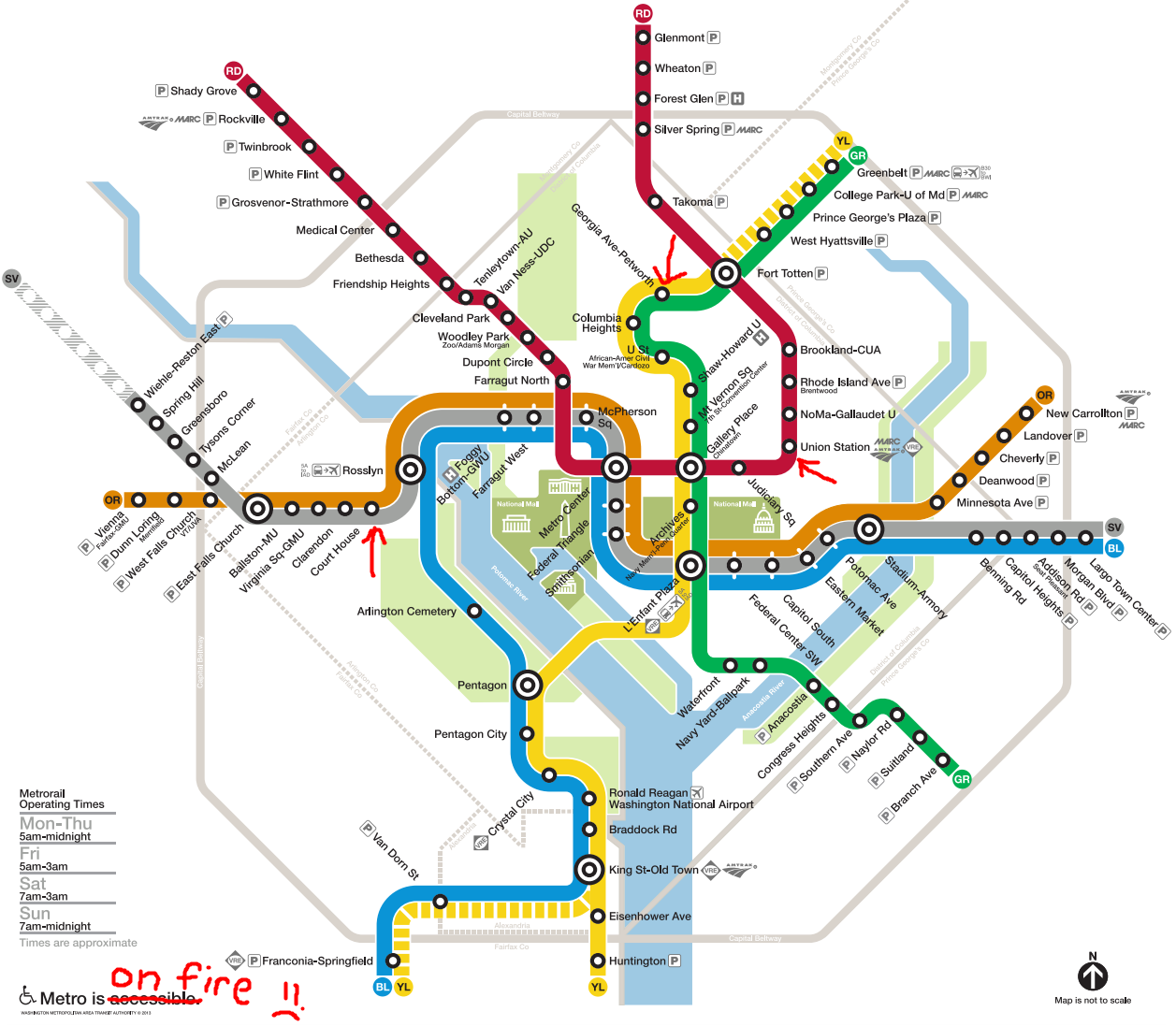

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) has a hard time keeping its trains on the “not” side of the “aflame” spectrum, so I was surprised to hear that they had an open API. You can check out the documentation for that api here. They were pretty quick to get me an API key and my experiences using it so far have been roundly positive (a far cry from my commuting experiences).

Goals

Every day I take the metro to and from work. Generally speaking, I’m leaving from my house (the Georgia Ave-Petworth Station to either Union Station or the Courthouse Metro Station. If you leave the navigation to google, you would almost always take the yellow (Y) or green (G) line south-bound for either destination, and then switch to the red (R) at Gallery Place (for Union Station) or to one of the orange (O), blue (B), or silver (S) lines at L’Enfant Plaza (for Courthouse).

But is google right? Is that actually the best choice? Inquiring minds want to know, so inquiring minds scrape the shit out of the wmata API for a few inquiring weeks and inquiringly calculate some inquiring statistics with inquiring math.

My main goal is to quantify what the average and extremal trips to either destination look like for all possible (okay, possible but not idiotic, no trips to Old Town on the way) routes, perhaps as a function of the week day and time. I’ll start with the Union Station trip since there are really only two paths (YG to Gallery Place and R to Union Station or YG to Fort TaterTotten and R to Union Station), and then take lessons learned there into the more complicated Courthouse trip.

Finding Data

Unfortunately, WMATA is not keeping track of historic train location or arrival time information (at least, not as far as I could tell), so I guess I’ll do it. Geeze.

I wrote some dead-simple python code (i.e. requests, json, and psycopg, not scrapy or bravado and sqlalchemy) to do the scraping; that code is on github here (yeah, no README yet, I’m ashamed). So the plan of attack was to persist current train location data to a database at some regular interval for some extended period of time. At the time of writing this, the process which is doing that is still running and persisting data to a postgres database on an Amazon Web Services (AWS) instance.

Nitty-Gritty

This project ended up including a fair amount of new complexities and a few interesting (if ultimately unused) tangents. The rest of this post will be about the details of how I set up the infrastructure and processes to acquire the wmata api data. A followup post will dig into the analysis.

Infrastructure

In terms of infrastructure, my methods of acquiring (web requests with python and requests) and persisting (postgres) data are old hat for me at this point. I suppose you could make the argument I should try something new one of these days, and I also suppose you could shut the help up, hater. What I did want to do a little differently this time was to push my limits a bit on the use of AWS. I had a long-underutilized AWS instance already set up (a t2.micro instance type running a debian AMI that I think (hope?) I got from the official debian “store”, so I simply had to install conda and postgres. I added an entry to my ssh config file to make logging in easier. I had done that years before on the recommendation of a colleague in school and had no idea what I was doing at the time – what a difference a decade makes!

Setting up postgres locally was pretty easy

sudo apt-get install postgresql postgresql-contrib

Per the tradition of my people, I created an independent postgres user for this project (details in the project’s postgres bootstrap script) and authorized password login for said user by updating the local and remote entries in pg_hba.conf file (mental note: I should write a blog post on doing that sometime) (mental retort: yeah, this would be super useful and certainly better than the hundred thousand articles already written on the subject, or, you know, the docs). In all honestly, I almost always forget how to do this and waste a fair amount of time trying to log in. I’m sure there’s a best way to handle this (e.g. a pg_admin tool) that I should be using, so if this sounds like a situation that has never bothered you, let me know how you do it.

At the moment I’ve restricted the ipv4 login rules to work exclusively for my home ip address – it didn’t seem possible to do anything less restrictive. In any case, the end result is a postgres database to which a project-specific user has access from both the local AWS server and my home development environment. Dope Francis.

I should mention: in addition to having to wrangle all the postgres-specific configuration details, I also got some experience working with inbound traffic rules for AWS security groups. This was actually a pretty straight-forward point-and-click process. Long story short: I can now make direct connections to the postgres port directly from (and only from) my ip address. I’m not sure how I would have controlled that without AWS (e.g. setting up some sort of firewall rules on the debian server itself), but I can’t imagine it would have been much easier than what I had to do here.

Getting Data

It’s hard to say more than the code can, so obviously I will try. I made a mental separation between the act of acquiring data and persisting it, and created object interfaces for those concepts. I assume that we have a WMATA parser object and a postgres publisher object, and individual API endpoints get their own API interface which inherits from each of the above. It probably would have been smarter to invert control (I think that’s the phrase) here and create a generic scraper object which took a parser and publisher and called methods from their interface, but I’m not that smart and double inheritance felt l33t in the moment.

Because the WMATA API exposes some swagger specifications (check out the Train Positions specification, for example), I briefly toyed with the idea of using one of the python swagger-spec-to-object libraries. I tried out Yelp’s bravado package at first, and really liked what was going on there at first glance. Unfortunately, however, it looks like WMATA didn’t fully complete their specifications (e.g. they didn’t create a response specification for status code 200 replies for the Standard Routes endpoint, one of the reasons you must ignore validation if you want to build the swagger client at all). I will definitely consider swagger and bravado for future API projects, but for the moment it’s probably more pain than it’s worth.

Finally, because I wanted to poll train positions at steady sub-minute intervals, I had to roll my own suuuuuuuuuper hacky polling mechanism. I would have loved to have used cron, but cron jobs can only be executed in minute intervals and I wanted finer resolution to my time dimension than that. I could have used a more formal polling library in python, or installed an external cron-like unix package, but instead I did this:

while True:

time.sleep(10)

try:

tp.publish(tp.get())

except Exception as e:

logger.exception(e)

Yeah… I feel dirty.

Persisting Data

There actually isn’t a whole lot of interest to say here – I had very simple tables to create in postgres (the schemas of which were determined exclusively by the WMATA API anyway), and psycopg2 did most of the heavy lifting in terms of creating and managing my database connections. For credentials management, I did something I’ve grown pretty fond of by now: I put credentials into a YAML file located in a separate, un-VC’d directory on my local machine, where the file permissions are locked down via the operating system.

About the only novel thing I did in persisting data was scrape the data in a local python session and publish it to the AWS instance remotely from there, but that was more of an infrastructure feat than a database feat.

Summary

WMATA had data, they gave it to me as json blob GET requests. I flattened those blobs, added timestamps, and inserted them into postgres with very simple INSERT statements.

Speaking of how simple those statements were, it occurs to me now that I didn’t create any primary key constraints on the one-time tables. That was a mistake. I should go fix that. Github issue time! That’s all I’ve got for now, check out the follow up post (if I ever write it, of course)!